Our last column ended with the question: “How do we get the economically vulnerable to care about water management?”. In this, the concluding piece, let’s see if we get to an answer.

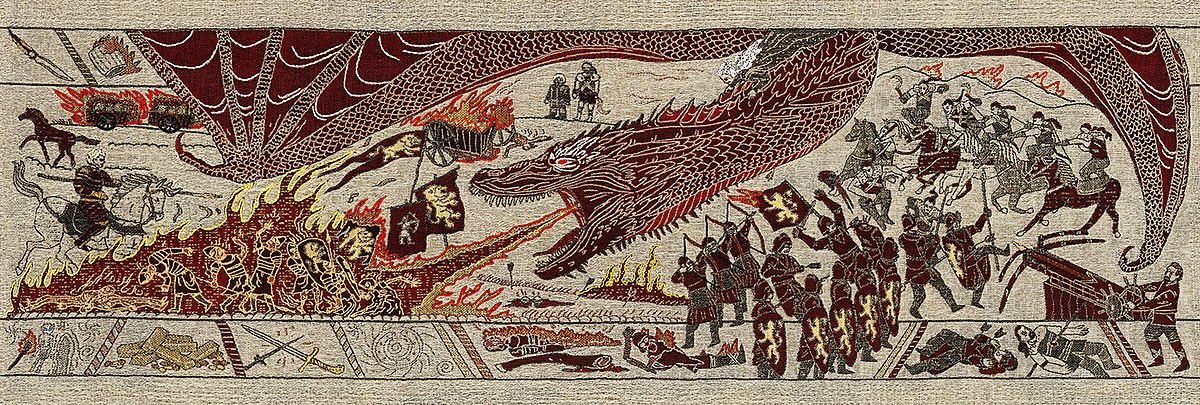

Warning: Spoilers Ahead! For those fans of ‘Game of Thrones’ (and apologies to those who don’t – skip to the end of this paragraph), there is a conversation between the Daenerys Targaryen, who has, at great personal cost, helped rid Westeros of the threat of the undead, and Missandei, her advisor. Missandei says that the people of King’s landing (and Westeros) will be grateful to Daenerys and will support her claim over Cersei, the current occupant of the Iron Throne. Daenerys responds that Cersei will never let the people believe that Daenerys saved them, because, she, like all effective rulers, understands the key role of spin.

The importance of spin, or narrative cannot be overstated in a democracy– not just in crafting the message, but, in our echo-chamber world, in also selecting the appropriate messenger and the medium are as important. Today, popular narrative spins ‘Provision’ as being poor-friendly. That must change if we want to make water management resonate with the voters.

Changing the Narrative: From ‘Provision as Poor-friendly’ to ‘Provision as Unfair’

Consider an expensive ‘provision’ for farmers –setting the Minimum Support Prices (MSP). The government allocated more than Rs. 1,15,114 crores towards the Department of Food and Public Distribution in 2016-17. This works out as annual subsidy of more than Rs. 12000 per agricultural household. That’s a big-ticket provision which addresses a key voter issue – better prices for agricultural produce. But does it really?

What many of us don’t appreciate is that many (most?) small farmers do not even know what the MSP of their crop is, and if even if they did, it’s at best a theoretical, out-of-reach concept, as most of the small farmers sell their crop to private traders.

In the same vein, the Rs. 11,000 crores that Maharashtra allocates annually for electricity subsidies reach a tiny percentage of larger farmers who own borewells – they don’t benefit small and marginal farmers. To wit, only 18% of Maharashtrian farmland is irrigated!

So why is this narrative persisting? We will answer that in a bit.

Changing the Narrative to ‘Provision cannot last’

Recently I was asked if the more economically vulnerable sections of our population understand what climate change is. It’s an important question. My answer was that they understand it far better than those of us leading air-conditioned cocooned lives. But I’m less sure that they understand the mechanism – that the warming is caused by greenhouse gases generated by development that has passed them by. That the disasters they see around them – flooding, unseasonal rain, drought, intense and increasing heat – will get worse. Fani highlighted the dangers of too much water and wind – while it will take a while to get the specific attribution of whether or not Fani’s power derived from a warmer climate, what is more settled is that a warmer climate makes more powerful storms more likely. Will provision work in such a world?

Moving to our cities, today, the informal residents, powerful and local councillors conspire to encroach flood plains and erstwhile water bodies. This made/makes sense for now. But with annual flooding becoming a reality in many Indian cities, will this equilibrium hold?

Burning of rice residues in SE Punjab, India, prior to the wheat season.

Moving to a key voter issue in Delhi: Air Pollution. Subsidizing power for farmers in Punjab to grow rice for the rest of us to eat made sense. But when Punjab cancels water-sharing agreements because it does not have enough water to lavish on its rice and wheat crops, does it continue to make sense? When burning the rice straw to speedily make room for the wheat crop results in the smogging the capital, does holding to a procurement target and an MSP make sense for paddy grown in Punjab?

The two buckets-worth of water that comes on alternate days could become two-lota fulls every third day as our population rises, and millions pour into cities and we run out of groundwater. In such a world, which we are just at the doorstep of, does the free-water of yesterday make sense? Our groundwater running out exposes the limits of the provision-centric-strategy in warming, populous, urban world.

Clearly provision cannot last. But how should an alternative narrative: ‘Management should be rewarded’ be spun, so that it will be listened to and believed?

Increasing the Timeframe

Management-as-a-narrative doesn’t stand a shot unless we increase time frame of our audience.

One way to do that is to reduce uncertainty in the economically vulnerable sections is by ensuring more regular incomes – i.e., an income-guarantee scheme. Please note, this needs to be targeted carefully – towards only the most vulnerable as they are the ones who are bypassed by the subsidy regime. Income transfers must be periodic – i.e., not a one-shot bonanza once a year, but a regular weekly or monthly trickle, which matches well with their cash outflows. Lastly, this income scheme must replace subsidies not be doled out in addition to subsidies. The last thing India needs is a ballooning deficit. But many pundits say the first rule of politics is that what has been given cannot be taken away. Perhaps, just perhaps, by giving something tangible and regular to the poorest, we can facilitate their support for cutting subsidies, especially when they find, in actuality, nothing is leaving their pockets.

Surveying political manifestos and recent political actions like the PM Kisan Samman Nidhi – we see that most political parties have jumped on to this somewhat-universal income bandwagon. But will such schemes cut the subsidies (as they ought) or kill fiscal prudence? We can only reflect on past political careers to make that call.

But there is no getting away from the fact that a more regular income is a necessity if we want our voters to look forward to increasing the pie rather than just dividing the pie.

Making the Story Resonate – Timing and make it local

A woman from Beed in Maharashtra could not care two hoots about a water price in Madurai – it would not get her to vote one way or another. But if she were to believe that charging Maharashtrian farmers for electricity would result in her not having to wait and fight for water in summer, she may lean in and say, “Tell me more”.

Water pricing is not ideally placed in national policy (but it was great to see it one political party’s manifesto) because water is a state subject, and as such the pricing decision is too. But in a dry city – like Chennai, for example, when it is reeling under the heat and most people are paying exorbitant explicit prices for water, pricing water through official channels by displacing private suppliers becomes politically sellable. Speak of the heroism of plumbers who fix leaks, of bureaucrats that repair meters, of school children who adopt a water body. In the summer, in a dry city, you will find a cheering audience.

Choosing the Narrator(s)

Who should sell this story to the voters? Not the political parties – because as per the 2018 Azim Premji/Lok Niti study, they are the least trusted. Would it be inappropriate for the most trusted – the military, the supreme and high court – to comment on this subject? Hmmm. Who else do Indians trust? That’s a crucial question – a Pew study suggests that Indians are quite trusting of their media organizations. But national media organizations spend a lot of time on national and state elections but spend far lower time on local issues. Could that change? Until it does, at a local level, the story could be told by local well-respected leaders and the civil society, who are likely to support solid initiatives in their own turf because they too will be impacted regularly by it.

The Roadblocks in moving local

There you have it – a good way to address the water crisis is to make it a local (municipal) compelling voting issue. But when moving action (i.e., moving to water management) and narrative to a local scale, we run into two road-blocks: money and talent. Many of us are trained to think of scaling up – scale up nationally, scale up internationally. As a result, talent migrates upwards where the money and the glitz reside. Bureaucrats begin their careers at the local level and move up nationally and internationally beckoned by power and glamour. Municipal management becomes hard when talent is scarce and budgets are comparatively tiny.

Enter civil society. Civil society can partner with the government to add capacity at the municipal level – to hold an honest mirror to the quality of service; to help design, plan and communicate; to work should-to-shoulder. The only problem is that the power/glamour issue operates powerfully on civil society too – many of them are in the Nation’s capital or in larger metros. Could (should) that change? To some extent, that is tied to the donor agenda.

Lastly, if municipal governments choose to price water, they can tap private capacity to deliver part of the service. Then, in F1 parlance, it’s game on!

To conclude, water is not a burning voter-issue – at least, not today, and not at the National level. To make water, and specifically water management, a voter issue at the local level, we can enhance municipal budgets and power (vive Amendment 74) and enlist civil societies to work with local governments and create a powerful, resonating narrative at a local level of the centrality of water, and its management in our everyday lives.

Given that we are in the midst of a national election, is there anything that the national parties can do to improve water resilience? Yes (but this is not a complete list). One is to indicate a shift in priorities – like what was done when the Prime Minister stood on the ramparts of the Red Fort and highlighted the importance of toilets. He made speaking of our sewage in public kosher. That’s a big deal. Another is the Swachh Survekshan, which infuses the spirit of competition into waste management and brings forth some transparency in the performance at municipalities. This is an idea that can be easily carted across to water. Third, there is an argument to be made for consolidating all roles into a single ministry/department so that decision making becomes easier. The last, but not the least, is the meaningful management of our forests – whose resilience we neglect at our own peril.