(A version of this piece appeared in Bloomberg Quint on Dec 02, 2018)

Case Study 2: Telangana

The politics of building water resilience – a problem of timelines

In Telangana, politics is water, and water defines politics, in a connection that stretches back through the sea of history. The Kakatiya dynasty, who ruled Telangana from 1163 AD to 1323 AD realised, like other kings of hilly, forested regions with temperamental, highly seasonal rainfall, that water storage held the key to prosperity. To that end, they built tanks – thousands of them. Tanks functioned alongside temples – the ruler or a noble established the tank as an act of charity, and the maintenance was left to the people, often with highly codified community responsibilities and rewards. This equilibrium lasted (for the most part) for centuries.

Shifting Equilibrium

This began to change with the British entry into India. Written in 1861, “Nizam – His History and Relations with the British Government, describes the Hyderabad principality thus:

“soil in general is extremely rich and fertile; and, except where the tanks have been allowed to fall into decay, the country is well watered.”

It appears the British did not appreciate the beauty of cascading tanks. Instead, they appear to consider tanks an extravagance:

“individuals have spent enormous sums of money in the construction of tanks, from the childish desire which the natives generally have of perpetuating their names for beneficence.”

The British philosophy was rooted in controlling natural resources, which manifested in command-and-control type of irrigation projects and massive deforestation. A series of devastating famines led to the construction of the Cotton Barrage, which made the Godavari navigable (and allowed easier transport of timber and cotton to the ports), while simultaneously creating a rice bowl in coastal Andhra Pradesh. With the focus firmly on canal irrigation, tanks began to lose popularity, and Telangana, her water storage. Even after the British left, Telangana continued to deforest rapidly, losing half its forest cover between 1930 and 2013. A lack of trees (and tree roots) meant less silt was held back, and more silt flowed down the rivers, making tank maintenance harder. Meanwhile the government continued to emphasize dam and canal over tank. This resulted in the shift of water resources from Telangana to other parts of Andhra Pradesh. Take the Krishna river. Within erstwhile Andhra Pradesh, while 69 % of the Krishna’s catchment area lies within Telangana, only 35% of Krishna’s water is allocated to Telangana while coastal Andhra with 13 % of the catchment area received 49 % of the Krishna waters. 79% of the catchment of the Godavari, the second longest river in India after the Ganga, lies in Telangana, but, here too, coastal Andhra became the major beneficiary.

There were other issues that shifted the equilibrium. In a cascading tank system, linkages are key; continual encroachment – both of the connecting channels and the tanks, together with a breakdown of the social systems lessened effective tank functioning: After all, why spend labour desilting a tank, when the water may not flow because a powerful upstream farmer decided to break the bunds, and take the water for himself?

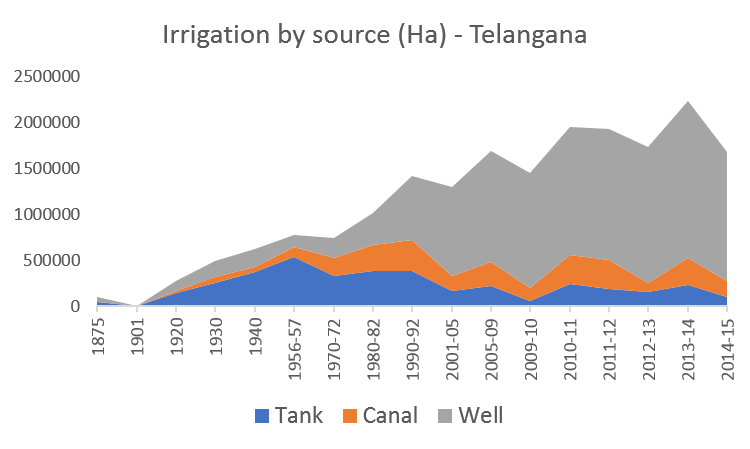

Hungry for water, farmers discovered a timely, technological miracle: the borewell. In a few decades, well and borewell assumed primacy in the irrigation systems of Telangana (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Telangana Irrigation by source; data from Pingle, G. (2011) & Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Hyderabad

But it was not enough: even today 63% of the crop is rainfed and exposed to the whims of the weather gods. A farmer with a 5-acre, rain-fed plot in Telangana looks to the sky and then downstream at the lush, irrigated paddy fields and bemoans his fate, and the priorities of his leaders. Given that 56% of the workforce is in agriculture, this envy translates to a powerful political force; A force that helped create the Telangana state and brought the Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS) to power.

System reset

Figure 2: Telangana Legislative Assembly, 2014, geographical representation by party (Wikipedia)

Figure 2 clearly shows that the TRS owes its ascendancy to the Telangana farmers. And that farmer’s profitability depends crucially on his/her crop choice, crop yield and crop price. Points 1 & 2 directly depend on water availability, making widening irrigation access a key thrust of the government. Renegotiating higher shares from existing large scale irrigation structures is unlikely to succeed, while building new major irrigation projects is expensive, lengthy, and runs into populist and environmental roadblocks because somebody’s home is submerged. Thus, major irrigation projects, while offering rent capturing opportunities, do not mesh well shorter political timelines. Enter Mission Kakatiya, the large-scale, revival of 46531 tanks, to improve the irrigation access of Telangana’s farmers. On paper, the scheme ticks several boxes – (a) it is farmer-friendly, (b) the timelines are far shorter – years vs decades – making it politically relevant, (c) there is no submergence of forest or village (removal of encroachments is another story), making it politically feasible, (d) done right, it improves water storage. The last point may seem a little technical, so let me explain. India, with its highly seasonal water supply, is woefully short of water storage, having only about 1/8th the world average per capita water storage. This is why tanks are brilliant. For one, they collect rainwater from the area they directly drain, and allow the rainwater a chance to percolate into the ground, rather than ‘runoff’. Second, a subset of tanks, called system tanks, are connected to a network of other tanks and to the river through canals. These system tanks are the beneficiaries of surplus non-local rainfall. During the southwest monsoon, the Godavari and her system of rivers swell as they capture the rain from their upstream regions. This surplus water flows through a set of channels to tanks, and as each tank overflows, downstream tanks, also connected via channels get filled.

Initially, as per all accounts, the mission worked well. Several international universities, including the University of Michigan and the University of Chicago started studying the project, with reported early findings being positive. The IWMI-Tata Programme reported positive effects on farm economics and groundwater, with a more nuanced impact on irrigation access from Mission Kakatiya when well implemented,. Other studies reported an explosion in fish production, benefiting the 1.9 million fishermen in the state.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the mission was perceived as a bold reset on water management. In 2016, a taxi driver, with roots in Mahbubnagar, was quoted as saying, “My father had tears in his eyes when he saw the tanks full. In his life, he hadn’t seen so much water. Some of us are even considering going back since there is now real potential in the fields”. The patchy data from the Water Resources Information System (some blocks are missing data for some years) supports his statement (See Figure 3). Mahbubnagar gave TRS 5 seats in 2014.

Figure 3: Groundwater level (metres below ground), Alampur, Mahbubnagar; 2017-18 not available.

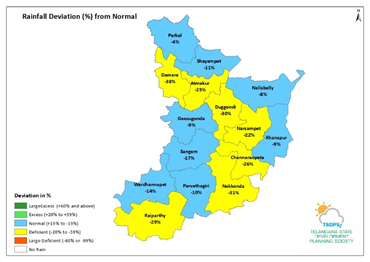

In Parkal block, in Warangal, small cotton farmers, owning land between 1-4 acres, sound happy today. This year, there is water enough for a second crop (Parkal had close to normal rainfall, see Figure 4) and they appreciated the silt (from the tanks) which raised their yields.

Figure 4: Rainfall map of 2018, Warangal Rural District

Here too, the groundwater data support their claims (See Figure 5).

Figure 5: Groundwater level (metres below ground), Parkal, Warangal; 2017-18 not available

Both Warangal and Mahbubnagar, had poor rainfall in 2014 and 2015, and above normal rainfall in 2016 (See Figure 4). This highlights the effectiveness of the scheme in 2015, while making the 2016 impact harder to call. Keep in mind, agricultural production, specifically paddy production has gone up steeply since 2015, showing there has been better water access.

Figure 4: Annual rainfall in mm in selected districts of Telangana (2014-2018)

Their Parkal farmers mentioned another thing: The Rythu Bandu scheme, which by directly transferring Rs. 4000 per acre helps alleviate working capital problems for farmers who own their land. These schemes (along with others like the drinking water scheme, important in regions plagued by Fluoride-rich groundwater) improve farmer resilience, which, as Telangana looks to be affected by climate change, makes this farmer-centricity a shrewd political move.

Losing Steam

Sadly, Mission Kakatiya appears to have lost steam. The strongest criticism/evidence comes from the Comptroller and Auditor General’s (CAG) office. The CAG report showed that while the completion rate of desilting tanks was a commendable 84% in Phase I of the mission, completion rates had fallen to 0 (!) by Phase III. This is supported by the Mission Kakatiya Dashboard. The scathing report states the mission could have

- coordinated better with MNREGA,

- planned the desilting of tanks during the non-rainy season,

- estimated the amount of silt more accurately, to ensure adequate desilting. To quote, “Average shortfall was 33 per cent … Thus, it could not be ensured that the storage capacity of these tanks was restored as intended in absence of proper mechanism to assess the quantum of silt to be removed and shortfalls in execution.”

- Prioritized the tanks to be desilted better. Ideally, system tanks with a dependable flow should be prioritised, so that desilting translates to better irrigation. However, to quote, “The sampled divisions could not produce any records with regard to assessment of dependable flows in tanks for prioritisation…None of the sampled division furnished list of chain linked tanks to Audit.”

This last criticism is echoed by others: system tanks, as their name implies, work as a system. If one does not desilt the connecting channels, and prioritise upstream tanks, desilting downstream tanks will not result in a higher irrigated area. One irrigation expert opined: “If something is done in the entire catchment, that will be useful, if some of the links are not covered, this is less helpful.”

This loss of steam was supported in some interviews. The driver from Mahbubnagar bemoans two years later, “Follow-up is poor, and implementation is patchy.” He is not planning to return now.

In Adilabad, where the TRS enjoyed an overwhelming victory in 2014, a young farmer growing 21 acres of cotton said “Ideas are simply super”, he said. “But it is not reaching the farmers. Many tanks are there, there are no connecting channels. These have been encroached”. The groundwater data, which is available only to 2016, could not be used to verify his statement.

Why is this happening?

In January 2018, the Telangana government offered 24 hour free power to farmers. This politically savvy move (Figure 1 shows wells are the primary form of irrigation in Telangana) helps explain the slowdown on tank irrigation. Groundwater access through free electricity is a quicker short-term fix. Until, of course, the groundwater runs out. In 2013, 30% of Telangana’s groundwater mandals were classified as unsafe. What are shrewd tactics for the current election, may not build longer term resilience of the state. The current manifesto shows short term focus (farm loan waivers, free housing etc.) has prevailed over even medium-term resilience building schemes. This does not bode well for the water or farmer-resiliency of India. Building resilience is a burning issue because Telangana ranks second in farmer suicides in India, and a recent study highlighted irrigation issues (including borewell failure) as a key cause.

Will the voter, the farmer, care? Maybe not, as their horizon, driven by high discounting rates, tends to be short. In truth, we must wait for the elections for the real answer.

(Afterword: Shortly after this piece was written, the Telangana Government won resoundingly, highlighting the difficulty of building water resilience through policy)

The need for a different approach

These experiences tell us to factor in political realities while framing solutions for our water crisis. For instance, adopting a hyperlocal approach in managing water often means the benefits accrue to those who bear the cost. This is politically “sellable” as it allows the best bang for the political-capital buck. Chemistry (the science) provides a useful way to think about water management. Many chemical reactions need energy to proceed. This energy, called the activation energy, enables a shift in equilibrium, along with another item, a catalyst, that often lowers the energy required. In proposing any water management solution, one can think of what is the catalyst, which will show us the right time to propose a solution, and what are the actions we can take to minimise the energy, or political capital/will required.

With this background, let us consider two solutions.